Devils Tower National Monument Continues to Captivate Crowds Over One Hundred Years After Establishment

A Native American prayer cloth hugs a tree close to the base of Devil’s Tower

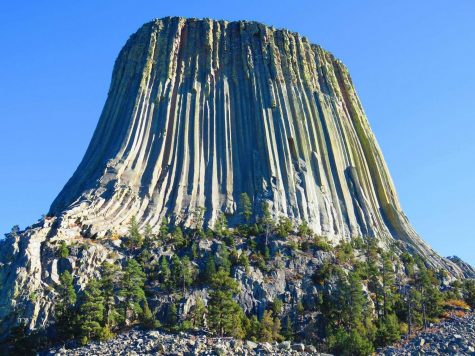

Rolling prairies and sparse, pine covered hills dot the landscape of western Wyoming, accompanying tourists and locals as they make their way down Wyoming Highway 24. A lone mountain range protrudes from the horizon far off the side of the road, almost lost in the white-blue haze of the afternoon. It is not the mountain, however, that they have come to see. For thousands of years a particular rock formation has drawn crowds from across North America and the world. The Devil’s Tower National Monument, which juts from the ground like the carved trunk of an ancient tree, is there to catch the eye of all whom near Wyoming Highway 10, no matter if they have come to see it or just pass through.

“I like to visit national parks in the fall and winter — less crowds and more peaceful. Earlier here you’d be standing shoulder to shoulder on the trail,” said Chris, an Interpretation Intern involved in SCA and Americorps.

Despite the off-season, cars from Illinois, Colorado, Virginia, North Dakota, Wisconsin, Ohio, Washington, Wyoming and Nebraska, competed for space in the yellow, oak-leaf-littered parking lot before the visitors center. The view that stood before them was explanation enough for the trip. A scarred Devil’s tower—hundreds of feet high—loomed above.

The grass and pine covered hillock that held the visitors center, as well as the Tower, quickly tapered and disappeared underneath the monument. Only the trees themselves continued into the rock-strewn boulder field that covered the majority of the Tower’s base. According to the U.S. Department of the Interior, the entire Tower stands at 1,267 feet tall, but the Tower itself stands at roughly 867 feet from its base. The Tower’s stone face appeared gray at first, but in the light of the afternoon October sun, both the face and base of the tower came to life with yellows, greens and reds.

“Lichen—a symbiotic relationship with lichen and fungus—that’s what makes the stone look green or yellow,” Chris, the Interpretation Intern, explained with a smile as he stood behind a desk inside the Devil’s Tower Visitor Center. While some may have been content with the view from the center, the majority of the people who had come moved in for a closer look.

“Wyoming is pretty barren on this side of the state so I was expecting more of that, but Devil’s Tower is pretty cool and I wasn’t expecting it,” said hiker and tourist, Nicole Lauren, when asked about the trail that surrounded the base of Devil’s Tower.

The boulder field, with rocks as large as a car, stretched out before a large portion of the Tower’s western face. Around its other faces stood a ponderosa forest that had been expertly maintained for decades. In this forest the quiet rush of wind lapping the plains and trees had been quite distinct. All the colors of the tower could be seen as one traveled.

Those same greens and yellows could be seen reflected in the pines and oaks that filled the area. Bolts of cloth, cast in greens, reds, yellows, blacks and blues, stood out from a few of the trees near the path. Each cloth pointed toward a deeper connection between people and the monument.

“I came here when I was a young kid and I remember I was in awe, so I wanted to experience it again,” said Steven Pasquerelli, another hiker who had visited the tower during his youth.

While Pasquerelli was certainly awed by the monument, Native Americans had been coming to the Tower and incorporating it into their oral history for centuries. The bolts of cloths that could be found in some trees beside the trail belonged to them and gave them a connection to a culture almost wiped out by European colonization. Those same Europeans would come to treat the Tower as a gathering place as well and sometimes drove cattle there from across the country.

In fact, the Tower left such an impression on these early settlers that, according to the U.S. Department of the Interior, President Theodore Roosevelt himself declared that Devil’s Tower would become the United States’ first national monument in 1906.

When asked about the formation of the monument itself, Pasquerelli said that he enjoyed “the mystery behind how it was formed. There is no way to know an answer about historical geology, so the different interpretations were interesting.”

Historical geology was indeed as open to interpretation as Pasquerelli had claimed. In fact, geologists can only assume what might have happened during the formation of Devil’s Tower. While other interpretations of the formation may exist, the U.S. Department of the Interior officially recognized three. Each interpretation varied slightly, but remained consistent in key areas. At one point some 50 million years ago Devil’s Tower had been a pocket of magma that slowly cooled into a plug. The monument seen today was gradually exposed through the process of erosion.

“It is isolated, very unique, and the columns are the largest in the world. It’s sacred to Natives, and leaves you in awe — so mysterious, so cool,” said Chris in an attempt to sum up his thoughts on the tower. Whether drawn to it through culture, adventure, wildlife, or geology, the Devil’s Tower National Monument remains one of the most visited locations in the Midwest.