Geraldine Warner, a second-generation American and Black Hills native, recently discovered an artifact that seemingly brought her father back to life: his historical photographs. Warner knew she had to take action to preserve the 100-year-old photographs of her father during his service in World War I and all the other memories he captured on film throughout his life.

Warner’s photo album was discovered by her son while cleaning out her apartment. Rather than throwing out the box and not recognizing what is inside of it, which happens too often, they looked inside and discovered the timeless treasure.

“There are so many [containers of photos], [that family members] just don’t realize that they’re throwing away from their mom’s and pop’s apartments,” Warner said.

Warner’s first step was to find a professional who knew how to restore them appropriately. This led to her meeting with Allen Morris, an assistant photography professor at Black Hills State University.

“I called the college and said to the gal, ‘How do I digitalize my photos,’” Warner said. “[The person on the phone] said, ‘Well I have a couple of people in mind who might be interested in a very old album that needs to be looked at’… I don’t think it was 20 minutes later [where Allen said] ‘I’ll take a look!’”

Warner and Morris’s first interaction started off with an immediate connection. “When I first came in he says, ‘The one thing I wanted in my whole life is that somebody walks in this place and blows me away,’” Warner said. “I said, ‘Well, I think I found it.’”

The two not only shared an appreciation for her historical pictures, but also developed a personal bond and friendship. They even joke about being related and how Warner will adopt him to be a part of her family.

“It has been an incredibly fun experience because the more Geraldine and I talk, particularly about our connected heritage in the formal Yugoslavia, the more we’re convinced we’re related somehow,” Morris said.

With a special bond, the transition of possession of Warner’s images to Morris was easier as they already established trust. Warner left the priceless photographs in Morris’s care.

When Morris analyzed the photographs, it was apparent that age started to get the best of the black and white images and it was a necessity to start the process of digitalizing them.

“I don’t think the original photos would have lasted a whole ton longer the way the book was decaying,” Morris said. “It was amazing they lasted that long.”

After gaining possession of the photos, Morris and BHSU photography intern, Sydney Robbinson, worked tediously over the summer with several tools and techniques to capture the photos for digitalization and presentation.

“The first thing we did was document the book,” Morris said. “We had this thing called a copy stand, which kind of like an easel with a camera that points down, and it takes photos of anything that is placed in front of it.”

This process was used for each photograph which involved special detail and effort as there were hundreds of pictures that underwent this process.

“We had somewhere in the vicinity of 260 individual photographs,” Morris said. “We scanned both front and back.”

The photos also had messages written on them which provided insight into where and what they portrayed, which helped in the documentation process.

“Some of the photographs had some writing on them,” Morris said. “We wanted to make sure that we could document that as well so if there was anything important [such as] names, dates, locations on the back that we were able to bring those together.”

After photographing the images, Morris and Robinson had to remove the photographs from a black construction paper that they were glued onto.

“What Sydney and I did is we used a bunch of different implements ranging from painter’s pallet knives that were super thin to get under the photo and dislodge the glue drops that were behind it,” Morris said.

This process did entail trials, however.

“Unfortunately, most of the black construction paper-type backing would stick to the back of the photo,” Morris said.”

This led Morris and Robinson to be creative in how to preserve the photos in glass frames by not damaging them any more than the age already did.

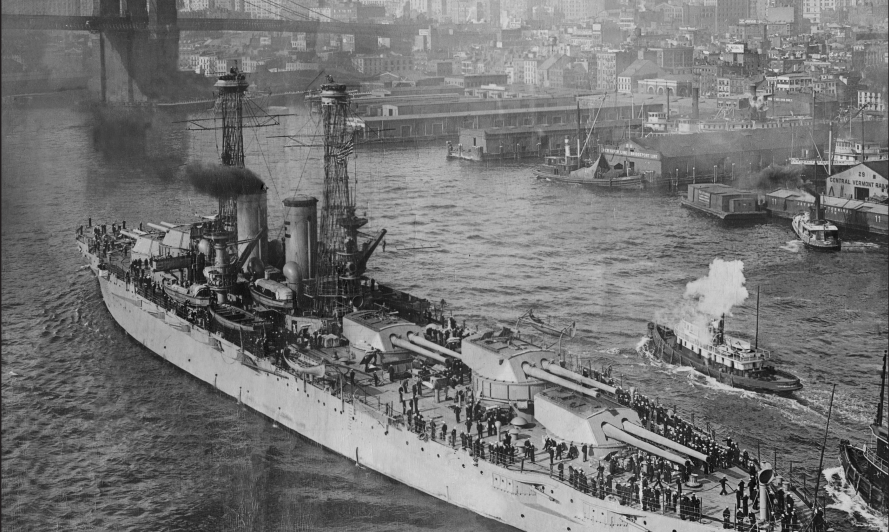

This was the case in particular with a photo of Jerry Batinovich, Warner’s father who served in the Navy during WWI on the USS Texas.

“The frame itself was brittle and when photographs are in a frame and there is not like a space between the photo and the frame itself the picture can actually stick to the back of the glass,” Morris said.

“There were a few bits of this image that were stuck, and I didn’t want to make it worse.”

Morris left the photograph in the frame and used his photography skills to avoid a reflection from the glass that would show up on the digital copies of the images.

“I am really happy with how it all turned out as we had to photograph everything through glass and avoid reflections and all of these complicated things,” Morris said.

Since the photo of the USS Texas included the Brooklyn Bridge in the background, Morris spent time using modern technology to fine tune details back into the photo.

“I was able to take it into Photoshop as it has a lot of age cracks that went through it since it dried out and there was paint or something on it,” Morris said. “I spent a good chunk of time cleaning it up and trying to find a nice balance between this as a historical photo and seeing some of the imperfections, but I wanted to clean up the ship and get rid of the red stains.”

The photos in the album of Warner’s father not only included his time in WWI, but also captured the life that he had outside of the military.

“Beyond being a war hero, and a hell of a good cook, he was also a photographer,” Morris said.

These details added just another element to how this project was based on more than just photos, but also showing off a life of a man. Batinovich’s love for cooking, for instance, was passed down to Warner. She used those skills to bake Morris banana bread as a gift. Working together throughout the summer created memories for Morris and Warner that they will now cherish.

After documenting and photographing the images, Morris and Robbinson wanted to make sure that they would be accessible for years to come.

“We wanted to make sure that when we did this that the photos got digitized, such as the front and back, so we had all of that information on record,” Morris said. “We scanned them at a really high resolution so any one of these prints, maybe two by four inches, could be printed to roughly 20 by 40-inch scale without any loss of quality— they’re big beefy files.”

The final step was to organize the images appropriately.

“Everything got organized and labeled based on their page number and where they are on the page,” Morris said. “We were able to collate the actual print to the digital file at the drop of the hat, and we now have all of this information available.”

Warner’s photographs were not only beneficial for her and her family, but they also contain priceless documentation for the community and for preserving historical moments in the Black Hills.

“I am extremely grateful that Geraldine and her sister Virginia and the whole family trusted us enough to let us basically take this thing apart,” Morris said.

By restoring this album, the images provide insight into moments that were captured in that time period, such as when the sailors came together not for just war, but to enjoy human experiences and how they also were just people who enjoyed life.

“We [captured] the Thanksgiving menu from the ship in 1916 and different WWI ephemera including the roster of officers on board during this Thanksgiving dance,” Morris said. “It’s funny to think of the levity of the people on the ship and how it was not always serious.”

But the photos also showcased the reality of war.

“WWI was one of the first wars that images were made publicly acceptable fairly quickly,” Morris said. “I was able to load these [images] up and there was nothing particularly gruesome, but it’s interesting as it gives us a little bit of insight and context of what it was like.”

In addition, the album contained pictures of Warner’s father which she holds dear to her heart, and the memories that they shared.

Now, the photographs are not only going to be able to be appreciated by Warner, but by anyone interested in U.S. history.

“I am happy to say we sent a thumb drive to the WW1 images to WW1 Museum in Kansas City,” Morris said.

This tedious process over the summer was not only special in that it saved a historical treasure, but it also created a beautiful friendship between Warner and Morris.

“It was truly an amazing experience to go through this process with an amazing group of humans, and I still can’t believe they trusted me to do this,” Morris said.

Warner shared a similar sentiment after working with Morris. “I wouldn’t have had anyone else in the world to do this [project],” Warner said.